Dear Diary,

Reading my very old diary seems like a perfect way to celebrate Valentine’s Day, a time for nostalgia and love. Diaries go along with flowers, candy, lace-trimmed red heart-shaped cards, romance, passion, flirting, secrets and wide-eyed innocence. And diaries are where we reveal our true love. But so far, reading you, dear diary, leads me to just the opposite–shame, embarrassment, and sadness.

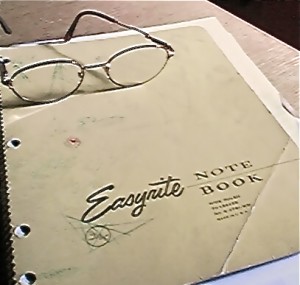

It was June 9th, 1962 when I began this diary. I had a new bright yellow Easyrite notebook, all the pages blank. However, I wrote my first entry on the last page, following my penchant for doing the opposite, the unusual, a habit I had perfected.

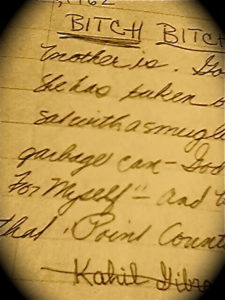

“BITCH BITCH BITCH,” are the first three words I wrote and now read. The words are in capital letters, underlined three times. I’m sorry to admit that my mother is the object of my fury. Why am I so angry with her? Putting it simply, we had a love-hate relationship.

That June day I was furious because my mother had “banned” yet another of my precious books, yet again torn it up and thrown it in the garbage. The book my mother threw out three days after my high school graduation was Norman Mailer’s “Advertisements for Myself”. In the first paragraph I made a list of the other books she’d thrown in the garbage can. They included Andre Gide’s “Point Counter Point”, Aldous Huxley’s “Barren Leaves”, Proust’s “Remembrance of Things Past” and something by Kahil Gibran which might have been saved because his name is crossed it out.

When I realized what she had done, I rushed down the driveway to retrieve the book. I remember those garbage cans standing in the alley at the foot of the driveway behind our newly built two-story red brick house on Fairlawn St. All along the alley were backyards like ours with only a few lawns, mostly coppery, yellow dirt left from the tractors of the construction crews bulldozing this new small subdivision in the East Hills. The street dead-ended at an open woodsy area where I walked my dog and seven years before read the complete Sherlock Holmes in a tree by a stream where violets grew.

Oh, I was seventeen and unsatisfied, lovelorn and resentful, rebelling against my parents and their expectations, contemptuous of the status quo. My only recourse was books, their wonderful stories, and from them I fashioned the story I desperately imagined for myself. Obviously, my mother suspected that these books were corrupting me and would not fit me for success. Maybe she blamed the books for my lousy, jaded, faux-superior attitude? Maybe she wanted her first daughter to be as sweet as those pink, lacy, Valentine cutout cards?

But I had decided I was beyond romance. I had read “Gone With the Wind” too long ago. Now I was desperately yearning for significance, wanting to be grown-up and a real writer too. I think I was hoping that if I were angry or bitter or isolated enough I’d feel as important as the characters Dostoevsky, Hemingway or Charlotte Bronte wrote about. In the poetry of Keats and Sylvia Plath and Dylan Thomas, I took “love” to mean “loss” and “desire” to mean “despair”.

Everyone knew those Valentine cards were corny, didn’t they?

After I graduated from an all-girls Catholic high school, I felt like I lost my school friends. My boyfriend, with whom I was desperately in love just like those Valentine cards promised, disappeared from my life. I thought I should leave everything I loved behind. Angry and bitter, hard and brutal were the desirable characteristics of the new adult world I saw I must enter.

Hell. Death. Suffering. These were the important words. On the back of my diary I had printed in a quivery hand three quotes from some famous philosopher that I don’t recognize: “Hell is the inability to love. Death is the inability to hope. Suffering is the inability to believe.” I thought if I could embrace hell, death and suffering, I’d be important too!

But the irony did not escape me. I was nothing if not ironical. I confess, dear diary, all I glean from reading you now is the contempt I felt for myself then. Who dared to care about that bookish seventeen year old girl from the comfortable suburbs of Pittsburgh in no apparent danger or distress?

I admit I’d love now to read more scenes like my first angry one. But “BITCH BITCH BITCH” may be the only really compelling line in the whole diary. I don’t know because the truth is I can only bear to read a little at a time. Dear diary, I confess you are boring and repetitive, empty of any meaningful characters or memorable details. Each sentence requires that I step back and forgive myself for my unpleasantness and the insufferable righteousness I claimed for myself while blaming my mother. Such tortured, melodrama! I guess I thought I was a true romantic.

Now I promise to read you. Taking my cue from the Buddhist practice of meditation, I will become aware of all that isn’t said, all that is bungled or disguised. Reading you will be my challenge–my practice, like the practice of zazen. Think of me sitting on a pillow, naming my thoughts and letting them go while I read on. You, dear diary, hold all I have left of that lonely teenager who was myself. I want to embrace that girl.

Maybe I could fall in love with her.