This was to be my first ever reading in my old hometown of Pittsburgh, PA and I was returning not only for this event but also for the reunion of Sacred Heart High School, Class of 1962. I’d be reading from my latest novel, Dreamers, A Coming of Age Love Story of the ‘60s, a story that echoes and frames my own childhood like an old family photo album.

The sky was a perfect blue, made bluer by the white puffy clouds floating between skyscrapers. My son, Jonas, also participating in the reading, led me down historic Liberty St toward Awesome Books. The light through the fall leaves on the tree-lined sidewalk radiated with pure possibility. A Columbus Day Parade was marching by as we walked into the bookstore for the first time.

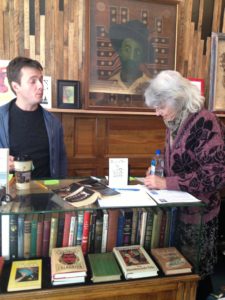

Awesome Book Store is a small, vintage, independent bookstore, classical in style. Every item–counter, cash register, bookshelves, tables, chairs, and the books themselves–was carefully placed for maximum artistic effect. There was an old typewriter casually positioned on a small wicker chair below a framed sign promoting future book events. Large, well-shined wood tables held all the latest titles of books I yearned to read.

Where would I be reading? The Awesome clerk, Dan, motioned me to a door, part way open, in the back where the event would be held. Inside I found a dark room, dreary, nearly empty too, cold and gray and windowless with a swath of scribbled brown paper on one wall, a bookshelf, a mirror and lots of boxes. It reminded me of the old coal cellar in the basement of my house on Foliage St. There was a small circle of green folding chairs set up surrounding a circular card table below one overhead light bulb.

The starkness emphatically spoke to the economic precariousness of independent bookstores working on a shoestring in this age of corporate, internet book aggregates.

This was not a medieval dungeon such as appears in any popular fantasy novel. It could have been Les Miserables, La Boheme or another romantic musical. Yet it felt so familiar and spoke to those deep stark roots where Annie and Thomas, the main characters in Dreamers were born. Maybe it was that dungeon where I locked myself in all those years conjuring up Dreamers I thought.

But even so, a dungeon is a dungeon, but dragons are both different and personal. My dragons were spewing their usual fire, taunting me with gloomy predictions; you’ll have no audience, no books sold. You’ll fall flat on your face. You’ll get dizzy and confused. And so on. The flames were full of general, debilitating angst.

Still, looking around, I realized that this small room reminded me of something else–the dark, cold inner circle of the Native American sweat lodge that I write about in Sundagger.net. It would be empty too, barren and cold before the door was shut, before the hot stones were brought in, and before the singing and drumming began. Here appearances meant nothing.

This was a place of purification, where all distractions were eliminated, where all that mattered was the story.

I began my reading by saying, “You are my hardest audience.” Oh, I could feel those dragons hanging from my neck. Facing those classmates of long ago and my family from far away, you could say I had more to lose here than in any other place I had read.

But my dragons were just ghosts. The audience filled the room in a very big and inspiring way, like the sky outside on that beautiful October day. I had no doubt we were together again for a reason. Listening to my son bring alive the powerful role of Thomas, I felt free of both dragons and dungeons too, transported into that space where I wrote the book. It was the ‘60s again, when the Civil Rights Movement was at its height, when all was romance, epic and life-changing, and dreaming was as common as breath. I had come home at last.